Data Types¶

NoneType¶

The sole value of the type NoneType is None.

The None value represent something which is unknown, undefined,

None is also frequently used to represent the absence of a value as when default arguments are not passed to a function.

>>> print(type(None))

<class 'NoneType'>

>>> a = None

>>> b = None

>>> id(a)

9568656

>>> id(b)

9568656

Note

the id() function returns an integer representing its identity (currently implemented as its address). so if 2 objects have the same id it’s the same object.

The None value is convert in boolean (see below) to False.

>>> bool(None)

False

Boolean¶

These represent the truth values False and True. The two objects representing the values False and True are the only Boolean objects. The Boolean type is a subtype of plain integers, and Boolean values behave like the values 0 and 1, respectively, in almost all contexts, the exception being that when converted to a string, the strings “False” or “True” are returned, respectively.

Integers¶

The size of an integer is limited only by the machine’s memory. So integers hundred digits long can easily be created and work with. Although they will be slower to use than integers that can be represent natively by the machine processor.

common numerics operators and functions¶

| Syntax | Description |

|---|---|

| x + y | Adds numbers x and y |

| x - y | Substracts y form x |

| x * y | Multiplies x by y |

| x / y | Divides x by y (be carefull there are some differences beween python2 and 3 see below) |

| x // y | Divides x by y; truncates any fractional parts to produce an int see also round() function |

| x % y | Produce the modulus (remainder) of dividing x by y |

| x ** y | Raise x to the power of y. See also pow() function. |

| -x | Negates x. Change x’s sign if non zero. if zero do nothing |

| +x | Do nothing. It’s sometimes used to clarify |

| abs(x) | Return the absloute value of x |

| divmod(x, y) | Return the quotient and the remainder of dividing x by y as a tuple of two ints |

| pow(x, y) | Raises x to the power of y. the same as ** operator |

| pow(x, y, z) | A faster alternative to (x ** y) % z |

| round(x, n) | Returns x rounded to n integral digit if n is negative int, or x rounded to n decimal places if n is positive int. The returned value has the same type as x |

Note

python2 vs Python3 regarding the division.

To highlight the before and after, let’s (re)define some terminology and their relationships and behavior with integer and floating-point operands.

Classic Division

This is the default division operator behavior in Python 2.x as well as in today’s dominant programming languages such as Java and C/C++. When presented with integer operands, classic division truncates the decimal place, returning an integer (also known as floor division). When given a pair of floating-point operands, it returns the actual floating-point quotient (aka true division).

Here is an example illustrating classic division functionality:

>>> 1 / 2 # integer truncation (floor division)

0

>>> 1.0 / 2.0 # returns real quotient (true division)

0.5

True Division

True division is where the result is always the real floating-point quotient, regardless of operand type. This is the default division operation in any Python 3.x release. As mentioned earlier, most Python 2 releases have both behaviors built-in; to take advantage of true division in 2.2 and newer 2.x releases, either start the interpreter with the -Qnew option or import division from __future__. Once you do that, the division operator ( / ) only performs true division:

>>> from __future__ import division # 2.2+ only

>>>

>>> 1 / 2 # returns real quotient

0.5

>>> 1.0 / 2.0 # returns real quotient

0.5

Floor Division

A new division operator ( // ) always truncates the fraction and rounds it to the next smallest whole number toward the left on the number line, regardless of the operands’ numeric types. This operator works starting in 2.2 and does not require the __future__ directive above.

>>> 1.0 // 2.0 # floors result, returns float

0.0

>>> -1 // 2 # negatives move left on number line

-1

Interger literals are written in 10 base by default but other number base can be used:

>>> 126 # decimal

>>> 0b1111110 # binary (with a leading 0b)

>>> 0176 # octal (with a leading 0)

>>> 0x7e # hexadecimal (with a leading 0x)

All the binary numeric operators (+, -, *, /, //, % and **) have an augmented assignment version (+=, -=, *=, /=, //=, % and **=) where x op= y is logically equivalent to x = x op y.

Floating Point types¶

Python provides thre types of floating point values:

float(built-in)decimal.Decimal(form standart library)complex(built-in)

All three types are immutable.

Float¶

The type float holds double precision foating numbers whose range depends on the native C compiler Python was built with.

They have a relative precision and cannot be reliably compare for equality. Numbers of type float are written with a decimal point

or exponantial notation.

>>> -2e9

>>> 8.9e-4

Coputers natively represents these numbers using base-2. This means some numbers can be represented exactly (such as 0.5) some others are only aproximately (such as 0.1 or 0.2). Futhermores this representation use a fixed number of bits, so there is a limit to the number of digits that can be held.

>>> 0.0, 5.4, -2.5, 8.9e-4

(0.0, 5.4, -2.5, 0.00089)

In some version of python (some old version python 2.6 or first version of 2.7 or version 3.0) the output can change sensibly:

>>> 0.0, 5.4, -2.5, 8.9e-4

>>> (0.0, 5.4000000000000004, -2.5, 0.00088999999999999995)

But what ever is the output the internal representation is the same and is just an aproximation.

This is not specific to Python, all computing language have the same whith the floating point numbers.

If we need high precision we can use int and scale it when nessecary or use the Python decimal.Decimal numbers from the decimal module.

Decimal¶

A decimal number is immutable. It has a sign, coefficient digits, and an exponent.

To preserve significance, the coefficient digits do not truncate trailing zeros.

Decimals also include special values such as Infinity, -Infinity, and NaN.

The standard also differentiates -0 from +0.

Decimal is not buil-in it belong to the module decimal, that mean we must import it before to use it. This means also that we cannot create directly a decimal number as floating point just writing them with a decimal point, we must use the Decimal constructor to build a decimal objects. Decimal instances can be constructed from integers, strings, floats, or tuples. Construction from an integer or a float performs an exact conversion of the value of that integer or float.

>>> from decimal import *

>>> getcontext().prec = 28

>>> Decimal(10)

Decimal('10')

>>> Decimal('3.14')

Decimal('3.14')

>>> Decimal(3.14)

Decimal('3.140000000000000124344978758017532527446746826171875')

>>> # From tuple

>>> # - The first value in the tuple should be an integer; either 0 for a positive number

>>> # or 1 for a negative number.

>>> # - The second value must be a tuple composed of intergers in the range 0 through 9

>>> # - The third value is an integer representing the exponant

>>> Decimal((0, (3, 1, 4), -2))

Decimal('3.14')

>>> Decimal(str(2.0 ** 0.5))

Decimal('1.41421356237')

>>> Decimal(2) ** Decimal('0.5')

Decimal('1.414213562373095048801688724')

>>> Decimal('NaN')

Decimal('NaN')

>>> Decimal('-Infinity')

Decimal('-Infinity')

The decimal module incorporates a notion of significant places so that 1.30 + 1.20 is 2.50. The trailing zero is kept to indicate significance. This is the customary presentation for monetary applications. For multiplication, the “schoolbook” approach uses all the figures in the multiplicands. For instance, 1.3 * 1.2 gives 1.56 while 1.30 * 1.20 gives 1.5600.

Unlike hardware based binary floating point, the decimal module has a user alterable precision (defaulting to 28 places) which can be as large as needed for a given problem:

>>> from decimal import *

>>> getcontext().prec = 6

>>> Decimal(1) / Decimal(7)

Decimal('0.142857')

>>> getcontext().prec = 28

>>> Decimal(1) / Decimal(7)

Decimal('0.1428571428571428571428571429')

for more examples see https://docs.python.org/3/library/decimal.html#quick-start-tutorial

All numerics operators and functions including their augmented assignment versions can be used with decimal.Decimal numbers.

But there is a couple of pitfalls. If the ** operator has a left hand decimal operand,

its right-hand operand must be an integer. Similarly, if the pow() function’s first argument is a decimal the 2nd and 3th arguments must be integers.

Although the division involving decimal is more accurate than ones involving floats, on a 32-bit machine the differences

only shows up after the fifteenth decimal place. Futhermore the computation using decimals are slower than those invloving floats.

So use decimals only if a high precision is required.

Complex¶

The complex data type is an immutable type that holds a pair of floats, one representing

the real part the other the imaginary part. Literal complex are written with the real and imaginary parts

joined by a + or - sign, and the imaginary following by a j. Note that if the real part is 0 we can ommit it entirely.

The separates parts of a complex are available through attributes real and imag.

>>> z= -89.5+2j

>>> z.real

-89.5

>>> z.imag

2.0

All numerics operators and functions are available excepting // , % , divmod(), and pow() with 3 arguments.

In addition complex have a method called conjugate, which change the sign of the imaginary part.

The functions in math module do not work with the complex numbers, if such operation is attemped an exception is raised.

But we can import cmath module which provide complex numbers versions of most trigonometrics and logarithmics functions

available in math module, plus some specific complex functions as cmath.phase() or cmath.polar() or cmath.rect().

Mixed mode arithmetic is supported as such that using int and float produces floats, and using

float and complex produces complex.

Because decimal offers fixed precision they can be used only with other decimal.

If an operation is attemped using imcompatible types a TypeError exception (Exception Handling) is raised.

Strings¶

Strings are represented by the immutable str data type which holds a sequence of characters.

The str data type can be called as a function (str()) to create string objects.

With no arguments, it returns an empty string, with a non string argument it returns the string form of the argument,

and with a string argument it returns the argument itself.

>>> a = "foo"

>>> b = str(a)

>>> a is b

True

string can be also create directly as literals. Strings literals can be enclosed in matching single quotes (‘) or double quotes (“). They can also be enclosed in matching groups of three single or double quotes (these are generally referred to as triple-quoted strings).

text = 'this a single quoted string which can include "double quote" but \'single\' quote must be escaped'

text = "this a double quoted string which can include 'single quote' but \"double\" quote must be escaped'"

The backslash () character is used to escape characters that otherwise have a special meaning, such as newline, backslash itself, or the quote character. String literals may optionally be prefixed with a letter ‘r’ or ‘R’; such strings are called raw strings and use different rules for interpreting backslash escape sequences. A prefix of ‘u’ or ‘U’ makes the string a Unicode string.

Unicode strings use the Unicode character set as defined by the Unicode Consortium and ISO 10646. Some additional escape sequences, described below, are available in Unicode strings.

In triple-quoted strings, unescaped newlines and quotes are allowed (and are retained), except that three unescaped quotes in a row terminate the string. (A “quote” is the character used to open the string, i.e. either ‘ or “.):

text = """this a triple quoted string which can include

- 'single' quotes

- "double" quotes without formality

This string allow several lines but support also newlines \

escaping, so this is very long line

"""

Python ASCII string escape

| escape | Meaning | notes |

|---|---|---|

| \ | backslash | |

| ‘ | single quote | |

| “ | double quote | |

| a | bell | |

| b | backspace | |

| f | formfeed | |

| n | linefeed (newline) | |

| N{name} | Character named name in the Unicode database (Unicode only) | |

| r | carriage return | |

| t | tab | |

| uxxxx | Character with 16-bit hex value xxxx (Unicode only) | |

| Uxxxxxxxx | Character with 32-bit hex value xxxxxxxx (Unicode only) | |

| v | vertical tab | |

| ooo | Character with octal value ooo | (3,5) |

| xhh | Character with hex value hh | (4,5) |

Notes:

- Individual code units which form parts of a surrogate pair can be encoded using this escape sequence.

- Any Unicode character can be encoded this way, but characters outside the Basic Multilingual Plane (BMP) will be encoded using a surrogate pair if Python is compiled to use 16-bit code units (the default).

- As in Standard C, up to three octal digits are accepted.

- Unlike in Standard C, exactly two hex digits are required.

- In a string literal, hexadecimal and octal escapes denote the byte with the given value; it is not necessary that the byte encodes a character in the source character set. In a Unicode literal, these escapes denote a Unicode character with the given value.

Unlike Standard C, all unrecognized escape sequences are left in the string unchanged, i.e., the backslash is left in the string. (This behavior is useful when debugging: if an escape sequence is mistyped, the resulting output is more easily recognized as broken.) It is also important to note that the escape sequences marked as “(Unicode only)” in the table above fall into the category of unrecognized escapes for non-Unicode string literals.

When an ‘r’ or ‘R’ prefix is present, a character following a backslash is included in the string without change, and all backslashes are left in the string. For example, the string literal r”\n” consists of two characters: a backslash and a lowercase ‘n’. String quotes can be escaped with a backslash, but the backslash remains in the string; for example, r”"” is a valid string literal consisting of two characters: a backslash and a double quote; r”" is not a valid string literal (even a raw string cannot end in an odd number of backslashes). Specifically, a raw string cannot end in a single backslash (since the backslash would escape the following quote character). Note also that a single backslash followed by a newline is interpreted as those two characters as part of the string, not as a line continuation.

When an ‘r’ or ‘R’ prefix is used in conjunction with a ‘u’ or ‘U’ prefix, then the \uXXXX and \UXXXXXXXX escape sequences are processed while all other backslashes are left in the string. For example, the string literal ur”\u0062\n” consists of three Unicode characters: ‘LATIN SMALL LETTER B’, ‘REVERSE SOLIDUS’, and ‘LATIN SMALL LETTER N’. Backslashes can be escaped with a preceding backslash; however, both remain in the string. As a result, \uXXXX escape sequences are only recognized when there are an odd number of backslashes.

Comparing Strings¶

Strings support the usual comparison operators <, <=, ==, !=, >, >=.

These operators compare strings byte by byte in memory.

>>> 'a' > 'b'

False

>>> 'albert' < 'alphonse'

True

The equality operator is == and allow to test if the string in right operand have the same value as the string in the left operand.:

>>> s1 = 'hello'

>>> s2 = 'hello'

>>> s1 == s2

True

Warning

Sometimes we are tempted to use is to compare 2 strings.

s1 = 'hello'

s2 = 'hello'

s1 == s2

s1 is s2

In this example we created 2 variables s1 and s2, and it seems that is allow us to compare them.

In fact we do not test the equality of the strings s1 and s2.

we test if the variables s1 and s2 point to the same object in memory.

see the following example:

s3 = ''.join(['h', 'e', 'l' , 'l', 'o'])

s1 == s3

True

s1 is s3

False

The operator of string comparison is == and not is (is is for object identity comparison).

So why it seems to work in the first example?

Python (like Java, .NET, …) uses string pooling / interning. The interpreter realises that “hello” is the same as “hello”, so it optimizes and uses the same location in memory.

Interned strings speed up string comparisons, which are sometimes a performance bottleneck in applications (such as compilers and dynamic programming language runtimes) that rely heavily on hash tables with string keys. Without interning, checking that two different strings are equal involves examining every character of both strings. This is slow for several reasons:

- it is inherently O(n) in the length of the strings;

- it typically requires reads from several regions of memory, which take time;

- and the reads fills up the processor cache, meaning there is less cache available for other needs.

With interned strings, a simple object identity test suffices after the original intern operation; this is typically implemented as a pointer equality test, normally just a single machine instruction with no memory reference at all.

So, when you have two string literals (words that are literally typed into your program source code, surrounded by quotation marks) in your program that have the same value, the Python compiler will automatically intern the strings, making them both stored at the same memory location. (Note that this doesn’t always happen, and the rules for when this happens are quite convoluted, so please don’t rely on this behavior in production code!)

Warning

In Python3, strings are encoded with utf-8, that means that some characters can be represented by 2 or more bytes sequence.

For instance, the character Å can be represented in UTF-8 endoded bytes in three differents ways:

[0xE2, 0x84, 0xAB], [0xC3, 0x85], [0x41, 0xCC, 0x 8A]. So before to compare unicode strings we need to normalize them.

import unicodedata

s = "Génétique"

unicodedata.normalize("NFKC", s)

(Complete api is accessible here https://docs.python.org/3.4/library/unicodedata.html#unicodedata.normalize)

The second problem is that the sorting of some characters is language-specific.

For instance in swedish ä `` is sort after ``z, whereas in German ä is sorted as is though were spelled ae.

To prevent subtle mistake, Python does not make guesses. It compares using the string memory representation.

This gives a sort order based on Unicode code points which gives ASCII sorting for english.

Slicing and Striding Strings¶

Python strings are sequences so we can access to any individual items, here characters, using the item operator square brackets []. Just to specify the index of the items between the square brackets. The index position start 0 and go up to the lenght.:

"protein"[0]

"p"

"protein"[3]

"t"

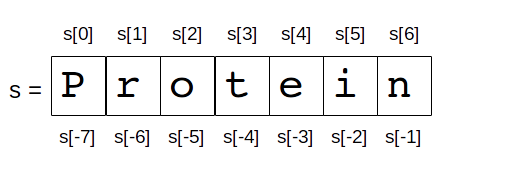

But it’s also possible to use negative index positions. These count from the last character backward to the first. Following an example of index positions for a the string s = “Protein”.

Negative index are very useful especially -1 which it give us always the last character in a string.

If we attempt to acces to an item out of the range (or any index even 0 in an empty string) an IndexError exception is raised.

Now we can acces any character of a string we want to access to several characters in one time. We call this slicing operation. The slice operator has three syntaxes:

- string[start]

- string[start:stop]

- string[start:stop:step]

the start stop step must be integers (or variables holding integers). We already see the fisrt syntax, the second syntax extract every characters starting at index start (include) to index stop (exclude). The third syntax is the same as the second except that instead of extracting every characters it extract every step-th characters. If a negative step is specify the slice is perform and the resulting string is reversed

>>> s = "Protein"

>>> # the second syntax [start, stop[

>>> s[2:4]

'ot'

>>> # note that if we ommit the stop index it will default to the end of string

>>> s[2:]

'otein'

>>> # we can also ommit the start index, then it will default to 0

>>> s[:2]

'Pr'

>>> s[3:-1]

'tei'

>>># we can omit start and stop

>>> z = s[:]

>>> z

'Protein'

>>>z is s

True

>>> s[1:-1:2]

'rti'

>>> s[::2]

'Poen'

>>> s[::-2]

'neoP'

>>> s[::-1]

'nietorP'

String operators and methods¶

Since strings are immutable sequences,

all the functions that can be used with immutable sequences can be applied on strings.

this include:

- membership testing with

in - concatenation with

+ - appending with

+= - replication with

*

>>> # Membership

>>> 'c' in 'gaattc'

True

>>> 'z' in 'gaattc'

False

>>> 'at' in 'gaattc'

True

>>> 'ta' in 'gaattc'

False

>>> # Concatenation

>>> 'gaa' + 'ttc'

'gaattc'

>>> s = 'gaa'

>>> s += 'ttc'

>>> s

'gaattc'

>>> # Replication

>>> s = 'a'*10

>>> s

'aaaaaaaaaa'

As strings are sequences they are sized objects. So we can apply the built-in function len() on a string. This will return the number of characters of the string.

>>> len('gaattc')

6

If there is more than 2 strings to concatenate the join method offer a better option. The syntax is sep.join(sequence of strings) this method join the element of the sequence of string in the argument and join them together into a single string using the sep as linking element. For example:

sequence = ['aa' , 'bb' , 'cc']

'<>'.join(sequence)

'aa<>bb<>cc'

''.join(sequence)

'aabbcc'

The join method can be used in combination with the built-in method reversed (which return a reversed iterator ) to reverse a string

>>> s = 'gaattc'

>>> ''.join(reversed(s))

'cttaag'

We already seen a more concise way to do that

>>> s = 'gaattc'

>>> s[::-1]

'cttaag'

If we are looking for the position of a substring in a string, we have two methods: index and find .

- index return the index position of the substring or raise a ValueError exception on failure.

- find return the index position of the substring or -1 on failure.

Both methods take the string to find as their first argument and accept optional arguments. The second argument is the start position in the string being search, and the third argument is the end position.

>>> 'gaattc'.find('c')

5

>>> 'gaattc'.find('c',0,4)

-1

>>> 'gaattc'.index('c')

5

>>> 'gaattc'.index('c',0,4)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ValueError: substring not found

for an exhaustive list of the strings methods: https://docs.python.org/3/library/stdtypes.html#string-methods

String formating¶

There are 2 ways to formats strings.

The old way using the operator % , it has been abandonned in python 3 in favor of the method format introduce in python2.6.

So, here we will describe only the format method

(the documentation on the % operator is available here).

The format method provide a very powerfull and versatile way to creating strings.

The format method returns a new string with the replacement fields in its string replaced with its arguments suitably formatted.

For instance:

>>> id = 'EcoR1'

>>> comment = 'restriction site 1 for Ecoli'

>>> seq = 'gaattc'

>>> fasta = '>{0} {1}\n{2}'.format(id, comment, seq)

>>> print(fasta)

>EcoR1 restriction site 1 for Ecoli

gaattc

Each replacement fields is identified by a filed name in braces.

If the field name is a simply integer, it is taken to be index position of one of the argumants passed to str.format().

So in this case, the field whose name was 0 was replaced by the first argument, and so on.

If wee need to include braces inside format strings, we can do so by doubling them up.

>>> "{{{0}}}, {1}.".format("I'm in braces", "I'm not")

"{I'm in braces}, I'm not."

As we saw, we can use format to concatenate strings but join is better for that.

format allow to perform conversion and concatenation in the same time. This is what format is made for this.:

>>> "e_value = {0:f}".format(0.12)

'e_value = 0.120000'

The replacement field can have any of the following general syntaxes:

- {field_name}

- {field_name!conversion}

- {field_name:format_specification}

- {field_name!conversion:format_specification}

Field Names¶

A field name can be either an integer corresponding to one of the str.format() arguments,

or the name of one of the keywords Arguments and Parameters

>>> fasta = '>{0} {1}\n{2}'.format(id = 'EcoR1',

comment = 'restriction site 1 for Ecoli',

seq = 'gaattc')

>EcoR1 restriction site 1 for Ecoli

gaattc

It can be also an item in a collection data types.

>>> ecor1 = ['EcoR1', 'restriction site 1 for Ecoli', 'gaattc]

>>> '>{0[0]} {0[1]}\n{0[2]}'.format(ecor1)

>>> ecor1 = {id : 'EcoR1', seq : 'gaattc, com : 'restriction site 1 for Ecoli'}

>>> '>{0[id]} {0[com]}\n{0[seq]}'.format(ecor1)

one very useful way to format string using mapping is to Sequence unpacking the mapping in the format arguments.:

>>> d = {'a' : 1 , 'b' : 2}

>>> 'a = {a}, b = {b}'.format(**d)

'a = 1, b = 2'

or a name attributes.

import math

>>> 'pi = {0.pi} e = {0.e}'.format(math)

'pi = 3.14159265359 e = 2.71828182846'

Conversions¶

Evry objects in Python have a representational form.

The pupose of this form is to provide a string which if interpreted by python recreated the object it represents.

For instance the representational form of sys module is the string <module ‘sys’ (built-in)>.

Some objects have a second form, a string form.The purpose of this form aimed at human readers.

All built-in data types have a string form. we can add a string form to our own object (this topic will not cover in this course).

If an object does not have string form python use the representational form.

In str.format we can force which representaion we want to use in our string there is 2 specifiers r for representational form or s

for string form.

>>> import decimal

>>> 'z as string : {0!s} or z resentational form : {0!r}'.format(z)

"z as string : 3.14159 or z resentational form : Decimal('3.14159')"

Note

In Python3 there is a third specifier: a to force representational form but in ASCII characters only.

Format Specifications¶

The default formating work well and can be fine for basic operation. But we can exercise a fine control on how the values formatted using the format specifications.

String¶

For strings, we can control the fill character, the alignment within the field, and the minimum and maximum field widths.

String format specifications is introduced with a semicolon(:) and has the following syntax

format_spec ::= [[fill]align][#][0][minimum width][.maximum width]

fill ::= <any character>

align ::= "<" | ">" | "^"

minimum width ::= integer

maximum precision ::= integer

string format examples:

>>> '{:30}'.format('minimum size') # minimum width 30

>>> '{:<30}'.format('left aligned') # minimum width 30 and left aligned

'left aligned '

>>> '{:>30}'.format('right aligned') # minimum width 30 and right aligned

' right aligned'

>>> '{:^30}'.format('centered') # minimum width 30 and centered

' centered '

>>> '{:*^30}'.format('centered') # use '*' as a fill char

'***********centered***********'

>>> '{:^.5}'.format('centered') # maximum 5 chars width

'cente'

Number (Integer, Float, Decimal)¶

The syntax for numbers is the same as for string but there is some specific fields.

format_spec ::= [[fill]align][sign][#][0][width][,][.precision][type]

fill ::= <any character>

align ::= "<" | ">" | "=" | "^"

sign ::= "+" | "-" | " "

width ::= integer

precision ::= integer

type ::= "b" | "c" | "d" | "e" | "E" | "f" | "F" | "g" | "G" | "n" | "o" | "s" |

"x" | "X" | "%"

sign: The sign option is only valid for number types, and can be one of the following:

| Option | Meaning |

|---|---|

| ‘+’ | indicates that a sign should be used for both positive as well as negative numbers. |

| ‘-‘ | indicates that a sign should be used only for negative numbers (this is the default behavior). |

| space | indicates that a leading space should be used on positive numbers, and a minus sign on negative numbers. |

# : option is only valid for integers, and only for binary, octal, or hexadecimal output. If present, it specifies that the output will be prefixed by ‘0b’, ‘0o’, or ‘0x’, respectively.

width: is a decimal integer defining the minimum field width. If not specified, then the field width will be determined by the content.

precision: is a decimal number indicating how many digits should be displayed after the decimal point for a floating point value formatted with ‘f’ and ‘F’, or before and after the decimal point for a floating point value formatted with ‘g’ or ‘G’.

type: determines how the data should be presented.

The available integer presentation types are:

| Type | Meaning |

|---|---|

| ‘b’ | Binary format. Outputs the number in base 2. |

| ‘c’ | Character. Converts the integer to the corresponding unicode character before printing. |

| ‘d’ | Decimal Integer. Outputs the number in base 10. |

| ‘o’ | Octal format. Outputs the number in base 8. |

| ‘x’ | Hex format. Outputs the number in base 16, using lower- case letters for the digits above 9. |

| ‘X’ | Hex format. Outputs the number in base 16, using upper- case letters for the digits above 9. |

| ‘n’ | Number. This is the same as ‘d’, except that it uses the current locale setting to insert the appropriate number separator characters. |

| None | The same as ‘d’. |

In addition to the above presentation types, integers can be formatted with the floating point presentation types listed below (except ‘n’ and None). When doing so, float() is used to convert the integer to a floating point number before formatting.

The available presentation types for floating point and decimal values are:

| Type | Meaning |

|---|---|

| ‘e’ | Exponent notation. Prints the number in scientific notation using the letter ‘e’ to indicate the exponent. The default precision is 6. |

| ‘E’ | Exponent notation. Same as ‘e’ except it uses an upper case ‘E’ as the separator character. |

| ‘f’ | Fixed point. Displays the number as a fixed-point number. The default precision is 6. |

| ‘F’ | Fixed point. Same as ‘f’. |

| ‘g’ | General format. For a given precision p >= 1, this rounds the number to p significant digits and then formats the result in either fixed-point format or in scientific notation, depending on its magnitude. The precise rules are as follows: suppose that the result formatted with presentation type ‘e’ and precision p-1 would have exponent exp. Then if -4 <= exp < p, the number is formatted with presentation type ‘f’ and precision p-1-exp. Otherwise, the number is formatted with presentation type ‘e’ and precision p-1. In both cases insignificant trailing zeros are removed from the significand, and the decimal point is also removed if there are no remaining digits following it. Positive and negative infinity, positive and negative zero, and nans, are formatted as inf, -inf, 0, -0 and nan respectively, regardless of the precision. A precision of 0 is treated as equivalent to a precision of 1. The default precision is 6. |

| ‘G’ | General format. Same as ‘g’ except switches to ‘E’ if the number gets too large. The representations of infinity and NaN are uppercased, too. |

| ‘n’ | Number. This is the same as ‘g’, except that it uses the current locale setting to insert the appropriate number separator characters. |

| ‘%’ | Percentage. Multiplies the number by 100 and displays in fixed (‘f’) format, followed by a percent sign. |

| None | The same as ‘g’. |

numbers format examples:

>>> import decimal

>>> z = decimal.Decimal("3.14159")

>>> "{:.2}".format(z) #format a decimal number with 2 digit width

'3.1'

>>> "{:.2f}".format(z) #format a decimal number with 2 digits after the dot.

'3.14'

>>> "{:012.1f}".format(z*10) # pad the left with 0

'0000000031.4'

>>> "{0:12.2e}".format(math.pi * 100) # display using exponential notation

' 3.14e+02'

>>> 'gc coverage = {:.2%}'.format(float(125)/230)

'gc coverage = 54.35%'

>>> # display percentage in python2 we need to convert one operand in float

>>> # to perform a float division

>>> # in python3 it's no necessary

For full description of strings formating see https://docs.python.org/3/library/string.html#formatstrings

Exercices¶

Exercise¶

Assume that we execute the following assignment statements:

width = 17

height = 12.0

delimiter ='.'

For each of the following expressions, write the value of the expression and the type (of the value of the expression) and explain:

- width / 2

- width / 2.0

- height / 3

- 1 + 2 * 5

Use the Python interpreter to check your answers.

Exercise¶

Write a function which take a radius as input and return the volume of a sphere:

The volume of a sphere with radius r is 4/3 πr3.

What is the volume of a sphere with radius 5?

Hint: π is in math module, so to access it you need to import the math module

Place the import statement at the top fo your file.

after that, you can use math.pi everywhere in the file like this:

>>> import math

>>>

>>> # do what you need to do

>>> math.pi # use math.pi

Hint: the volume of a spher with radius 5 is not 392.7 !

Exercise¶

Draw what happen in memory when the following statements are executed:

i = 12

i += 2

and

s = 'gaa'

s = s + 'ttc'

Exercise¶

how to obtain a new sequence which is the 10 times repetition of the this motif : “AGGTCGACCAGATTANTCCG”

Exercise¶

create a representation in fasta format of following sequence :

Note

A sequence in FASTA format begins with a single-line description, followed by lines of sequence data.

The description line is distinguished from the sequence data by a greater-than (“>”) symbol in the first column.

The word following the “>” symbol is the identifier of the sequence, and the rest of the line is the description (optional).

There should be no space between the “>” and the first letter of the identifier.

The sequence ends

- if another line starting with a “>” appears (this indicates the start of another sequence).

- or at the end of file.

id = "sp|P60568|IL2_HUMAN"

comment = "Interleukin-2 OS=Homo sapiens GN=IL2 PE=1 SV=1"

sequence = """MYRMQLLSCIALSLALVTNSAPTSSSTKKTQLQLEHLLLDLQMILNGINNYKNPKLTRML

TFKFYMPKKATELKHLQCLEEELKPLEEVLNLAQSKNFHLRPRDLISNINVIVLELKGSE

TTFMCEYADETATIVEFLNRWITFCQSIISTLT"""

Exercise¶

For the following exercise use the python file sv40 in fasta which is a python file with the sequence of sv40 in fasta format

already embeded, and use import sv40 in your script to work

(the sv40.py file must be placed in same directory as your own script).

Write a function fasta_2_one_line that return a sequence as a string

without header or any non sequence characters

Note

Pseudocode is an informal high-level description of the operating principle of a computer program or other algorithm.

Pseudocode is a kind of structured english for describing algorithms. It allows the designer to focus on the logic of the algorithm without being distracted by details of language syntax. At the same time, the pseudocode needs to be complete. It describe the entire logic of the algorithm so that implementation becomes a rote mechanical task of translating line by line into source code.

The pseudocode is:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/J02400.1

Is that the following enzymes:

- BamHI (ggatcc),

- EcorI (gaattc),

- HindIII (aagctt),

- SmaI (cccggg)

have recogition sites in sv40 (just answer by True or False)?

for the enzymes which have a recognition site can you give their positions?

is there only one site in sv40 per enzyme?

Exercise¶

We want to perform a PCR on sv40, can you give the length and the sequence of the amplicon?

Write a function which have 3 parameters sequence, primer_1 and primer_2

- We consider only the cases where primer_1 and primer_2 are present in sequence

- to simplify the exercise, the 2 primers can be read directly in the sv40 sequence.

test you algorithm with the following primers

Write the pseudocode before to implement it.

Exercise¶

- reverse the following sequence “TACCTTCTGAGGCGGAAAGA” (don’t compute the complement):

- using the shorter string s = ‘gaattc’ draw what happen in memory when you reverse the s

Exercise¶

il2_human = ‘MYRMQLLSCIALSLALVTNSAPTSSSTKKTQLQLEHLLLDLQMILNGINNYKNPKLTRMLTFKFYMPKKATELKHLQCLEEELKPLEEVLNLAQSKNFHLRPRDLISNINVIVLELKGSETTFMCEYADETATIVEFLNRWITFCQSIISTLT’

Exercise¶

Write a function

- which take a sequence as paramter

- compute the GC%

- and return it

- display the results readable for human as a micro report like this: ‘the sv40 is 5243 bp length and have 40.80% gc’

use sv40 sequence to test your function.